Thank you! Your submission has been received!

Oops! Something went wrong while submitting the form.

Historically, the existence of a (paper-based, shelf-situated, dust-attracting) corporate compliance program was considered by some as a proxy for its effectiveness in preventing and detecting criminal conduct. Towards the end of the last decade, advances in technology - particularly data analytics - elevated the expectations of U.S. prosecutors as to compliance program effectiveness, and the required evidence to demonstrate this. More recently, these expectations evolved further, focusing on a plan for the consistent and sustainable measurement of “the success and effectiveness” of a company’s compliance program.1

For U.S. corporate criminal prosecutions, this assessment of a company’s compliance program (including efforts to measure its effectiveness) is undertaken by prosecutors when determining (a) whether to charge a company for corporate wrongdoing; (b) whether to negotiate a plea or other agreement; (c) the criminal penalty discount to be afforded to a company, in recognition of its remediation efforts and improvements to a compliance program; and (d) the need for a corporate monitor.2 While the nature of U.S. criminal corporate enforcement going forward is currently unclear, there are other regulatory drivers for an effective compliance program.3 For example:

Moreover, new and overlapping compliance risks are reinforcing the need for a consistent and integrated approach to program design and assurance. For example, in recent years, we have seen the introduction of data privacy, cyber security and responsible artificial intelligence (AI) laws and associated compliance program guidance. A more holistic, flexible and less U.S./FCPA-orientated approach to the measurement of program effectiveness is required.

Stakeholders interested in the effectiveness of compliance programs now extend well beyond prosecutors and regulators. Ethics and compliance professionals are already familiar with responding to FCPA-driven questionnaires and books and records audits from customers. But the universe of stakeholders has expanded dramatically in recent years, and each have their own unique substantive and evidentiary requirements. For example:

But perhaps the most important stakeholder is you, the ethics and compliance officer. You and your team have invested significant time, energy, and political capital in building the compliance program. You want assurance that those efforts are delivering an efficient and cost-effective program that is working; one that can disincentivize, prevent, detect, and respond to conduct that breaks the law or your company’s values.

The inherently subjective and elusive nature of compliance program effectiveness is perhaps the reason it is the subject of so much debate. A starting point is to consider the desired outcome of a compliance program. At the most simplistic level, an effective ethics & compliance program is one that ensures that a company (including its employees and associated third parties) complies with the applicable law (compliance), and the company’s core values (ethics). But this clearly requires some unpacking:

Are Identified Program Breaches & Weaknesses Being Addressed?

These questions are illustrative, and by no means comprehensive. Some compliance programs may have goals that differ to the above, such as the modern slavery requirements of rightsholder consultation, remediation and public reporting mentioned above. This serves to reinforce the importance of actively considering the desired outcome of a compliance program, and the impact that has on its design and associated testing. We also challenge the concept that making a program more effective means doing “more” – in some instances, a program can be made more effective through simplification or even elimination of program requirements.

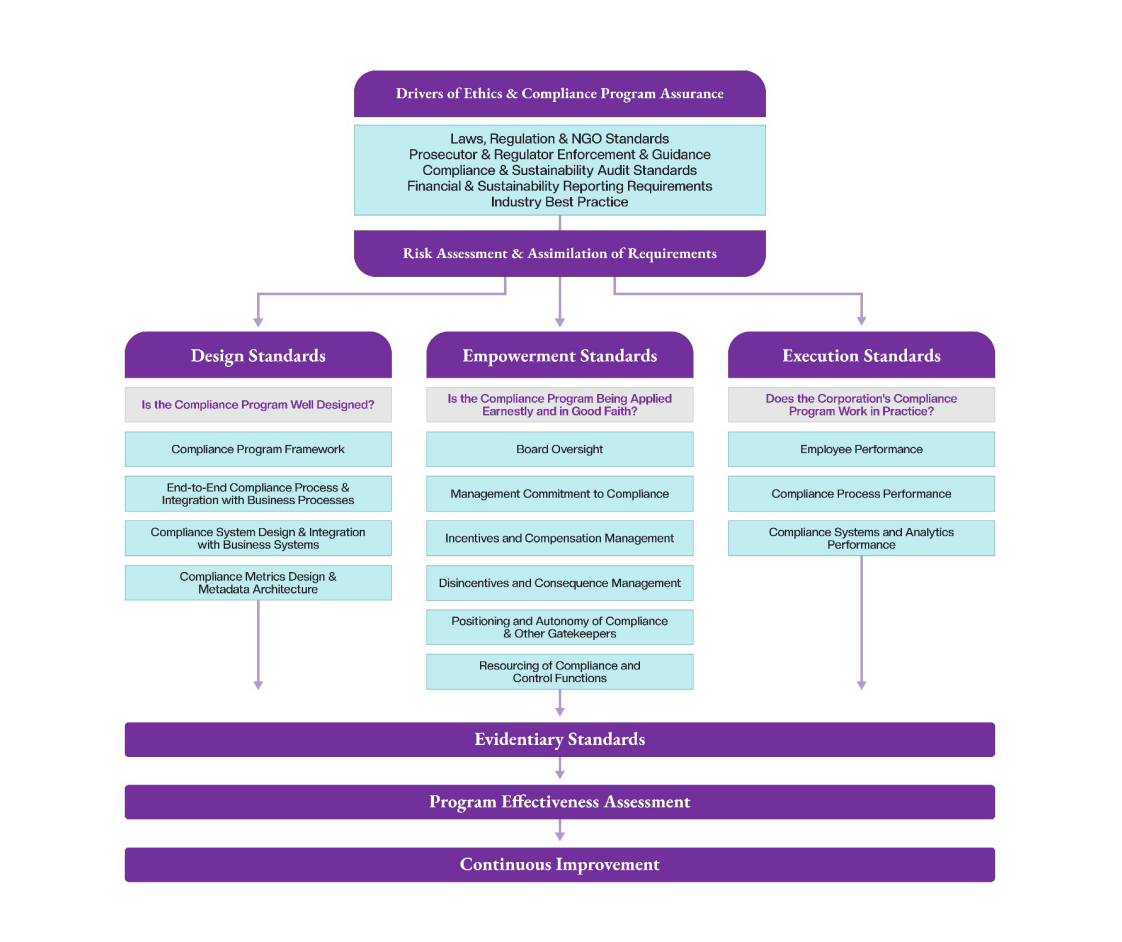

The U.S. DOJ’s Justice Manual (expanded upon by the ECCP) provides a helpful starting point for the effectiveness evaluation of any compliance program. The DOJ asks 3 foundational questions:

We refer to these effectiveness measures as Program Design, Empowerment and Execution respectively. Behind each of these three measures, there is an implicit fourth: is there Evidence to support this “measurement” of program effectiveness? If not, you cannot fully answer the three preceding questions.

Despite the increasing range of compliance program drivers and heightened evidentiary expectations, the way program effectiveness is evaluated has not kept pace. For example, program assessments have tended to be:

In this article, we advocate taking a more intentional, data-driven and technology-enabled approach to continuous program effectiveness assessment through:

This intentional approach requires conscious investment of time and resources. However, generative artificial intelligence (Gen AI) offers the opportunity to reduce this burden, and extract even more insights into compliance program effectiveness. Throughout this article, we highlight ways in which Gen AI can support your program effectiveness testing.

This article references the related concepts of compliance risk and cultural health assessments, to the extent that they serve as inputs to/beneficiaries of a program effectiveness assessment. Full treatment of these important topics is outside the scope of this article.

* This framework can also be applied to related business processes and systems (e.g., accounts payable, employee expense management and delegations of authority)

As indicated above, the traditional approach has been to assess programs at the ethics & compliance or substantive risk level (e.g., anti-corruption, antitrust). Such high-level assessments often fail to consider the design, and execution realities of individual program elements. For example, the practical management of anti-corruption risk associated with charitable donations differs to the management of vendors involved in government permitting processes. Moreover, the charitable donations program should not be solely assessed through an anti-corruption lens; such donations give rise to tax, reputational and other risks.

Adopting our recommended approach to program assurance requires time, focus, and engagement across the organization. It is neither practical nor necessary to apply this level of rigor across the entire ethics & compliance program all at once.

Instead, go narrow and go deep. Focus on a company’s highest compliance-risk activities and assess the specific program elements that manage the risk. Take the example of a global construction company that relies heavily on government-facing vendors to secure local building permits in countries with elevated corruption risk. In this scenario, an obvious candidate for program assurance would be the anti-bribery & corruption third-party due diligence program. At the same time, the company might also consider reviewing the effectiveness of related procurement and finance processes such as vendor qualification, competitive sourcing, and accounts payable.

Then move on to the next compliance program element. Over time, a series of maintained deep-dive reviews can collectively form a reliable basis for assurance across broader risk areas (e.g., anti-corruption). The table below provides a representative map of elements of an anti-corruption program that could be prioritized and tested according to the materiality of the bribery & corruption risk that they manage:

The remaining focus of this article will be the testing of specific compliance program and business process elements such as those listed above. However, it is worth noting that an enterprise level assessment of these program elements may also be merited. For example, an enterprise level design assessment of:

Having selected the program (element), what are the drivers of the relevant testing framework?

The design, empowerment, execution and evidentiary requirements of a compliance program are obviously driven by the relevant legal risk assessment.13 While the laws themselves rarely go into the minutiae of compliance program design, the enforcement practices and guidance of prosecutors and regulators form the foundation of program effectiveness measures.14

While not a substitute for legal advice, or constituting a full program effectiveness assessment, AI-driven gap assessments of a company’s existing policies and procedures against applicable regulatory frameworks are now being offered by several companies.

However, regulation, enforcement and government guidance are not the only drivers of program effectiveness; mindful of the stakeholders referenced above, there may also be quasi-legal, audit and other requirements that need to be considered:

Understanding the full design and evidentiary scope of these requirements enables your company to make a more informed decision as to the required time and resources to be invested in the applicable program, and the associated framework for measuring effectiveness.

Generative AI can play a role here supplementing pre-existing legal risk assessments by extracting and summarizing the design, empowerment, execution and evidentiary requirements of these other sources. For example, Gen AI can review existing contracts with customers or lenders to identify common and unique program and evidentiary requirements that need to be factored into your program design and testing.

In areas of compliance such as environmental or cyber-security, global audit standards (e.g., ISO, NIST) have been accepted as an assimilation of these various drivers into a proxy for program effectiveness. In contrast, for example, the ISO 37001 Anti-bribery management systems standard has gained less traction. Moreover, company’s SOX controls frameworks may not extend to all compliance controls, and certainly not broader standards of program effectiveness. In this assurance vacuum, the trigger tendency in ethics & compliance has been to move subconsciously straight from risk assessment to program design, governance in particular.

We recommend an intermediary step, assimilating these legal, enforcement, audit, reporting and other drivers - filtered through a company-specific risk assessment - into a tailored series of documented program design, empowerment, execution and evidentiary standards. In this regard, the design and format of SOX controls, ISO and other audit standards can help ethics and compliance professionals to curate their own program effectiveness standards that reflect their organization’s unique risk profile and operational reality.

For example, if your company’s antitrust risk is high, you may have decided to develop standards relating to employee participation in industry associations. Program design standards would likely include several relating to training, perhaps taken from US, EU and other guidance as well as industry best practice:

Empowerment standards might focus on management support for and participation in the training. Execution standards would include not only training completion metrics, but also employee feedback on the quality of training and the impact of the training on employee conduct during association meetings.

Since training is a type of control, one might observe that this is simply a form of control effectiveness assessment. That would be correct; however, the same type of effectiveness assessment can be applied to program design, empowerment and execution standards beyond controls.

How are these program effectiveness standards to be structured?

There is a tendency for companies to overly focus on program governance, tone from the top communications and employee compliance metrics as proxies for program design, empowerment and execution effectiveness respectively. We submit that the concept of compliance program effectiveness is broader. The table below shows the full scope of compliance program effectiveness, utilizing the DOJ’s design, empowerment and execution questions as a guiding framework. The same approach can also be utilized to assess the effectiveness of related business processes, systems and analytics.

We consider these elements, and the associated evidence, in more detail in Section D.

The traditionally narrower focus of program design audits may be a function of who has undertaken them. Outside advisors without prior in-house experience may not have a working understanding of how, in practice, compliance programs work in parallel with each other, or how they are embedded in functional processes and systems. Resulting assessments are reliant on surface-level documentation, tend to be generic in nature and do not offer granular, operational-level recommendations for improvement.

Similarly, simply relying on self-assessments by the relevant “subject matter expert” owner of a specific program raises questions about objectivity and may overlook opportunities and challenges where the program under review intersects with other compliance programs (e.g., corruption -> sanctions and antitrust).

True program effectiveness testing requires a broader team, with the appropriate blend of skills and experience, who can:

When designing your performance standards, it will often become clear as to who is best placed to test performance against each standard.

The utilization of program effectiveness standards allows you to identify upfront the evidence required to test whether your program meets each standard. Such evidence falls into several categories:

As part of their due diligence program, companies willingly send out detailed questionnaires to third parties asking them to describe their corporate compliance programs. In their diligence platforms, they will maintain and periodically seek updates to hundreds of these program narratives. And yet, curiously, such narratives are rarely maintained about their own compliance program.

Moreover, supporting documentary evidence of a program can only tell half the story. For example, compliance policies and training materials are rightly focused on the positive obligations and prohibitions that employees must follow. They rarely include a narrative as to how these materials were put together, who was consulted or how they are being administered in practice, nor should they. But this does not preclude the need for a contemporaneous narrative to accompany the policy or training material.

At the heart of program effectiveness assurance is the self-assessment narrative; an explanation of how your company is performing against program design, empowerment and execution standards. The person best placed to provide that program narrative is likely the program or process owner responsible for meeting the standard.

Continuing with the industry association antitrust training example, let’s focus on the narrative for the following design standard:

The employee roles to be assigned industry association antitrust training have been determined

The responsible person might document the following:

Industry association training is assigned to (a) all employees in external affairs; (b) all employees serving on an industry association board or committee; (c) all employees who are sponsors of company participation in the association. Compliance obtains details of new employees falling into these categories from external affairs, which is responsible for the company’s membership of industry associations. We are exploring opportunities to expedite the training assignment process in our Learning Management System, by automating the extraction of employee data from external affairs.

The act of preparing the self-assessment enables the responsible person to identify existing gaps, and area of planned improvement. The narrative does not need to be extensive, but it helps others to review how the responsible person is meeting the standard. For example, the chief compliance officer might provide feedback to the antitrust program owner that members of management above a certain grade should also receive the training, given the likelihood that they may participate in industry association events from time to time.

Program narrative is important but is not sufficient by itself. Assurance is also dependent on the consistent retention of supporting evidence, the nature of which is heavily dependent on the program element being assessed and the type of program assessment (design, empowerment or execution) being undertaken. Such evidence could include:

For program elements supported by compliance or other platforms, the collation of this information can be built into the process. For example, for due diligence of high-risk third parties, approval workflows could make the uploading of meeting minutes with senior leadership mandatory.

For other records there may need to be an intentional decision as to where they are maintained. Compliance tech providers (training, diligence, investigations) tend to be focused on the execution of their process rather than serving as the complete system of record for all supporting evidence of program effectiveness. In this situation, being clear as to where and how other supporting evidence is being filed and retained is critical. That all-important evidence needed in response to a future investigation or audit will not be found if it’s in the wrong place and has an unclear filename. Your colleagues in other functions with experience on managing SOX controls assurance or responses to ISO audits may be able to guide you here on best practices.

While the focus tends to be on metrics relating to employee compliance, metrics can serve as a proxy for the effectiveness of all aspects of design, empowerment and execution. This is addressed further in Section D

Here we focus on some generic considerations relating to metrics:

Generative AI has the potential to assimilate structured data (such as metrics) and unstructuredinformation to provide even richer insights as to potential weaknesses in program effectiveness or culturalhealth.

Metrics are inherently depending on supporting metadata. Some compliance platforms - such as training, due diligence, and investigations - produce structured data. This can be utilized within or exported from the relevant system and used in cultural health and compliance program effectiveness metrics.

Other compliance activity, particularly that administered outside of workflow platforms, generate unstructured information. In these cases, compliance teams should seek to identify and extract “micro-data” points that can be tracked and compared over time. For example, common measures of program execution effectiveness and cultural health relate to the level of employee engagement with the program. The program owner may already have metadata associated with employee completion of training and survey feedback on the quality of training. The owner might also have data relating to employee engagement with program governance from the company’s policy management system. But there are other potentially valuable data “nuggets” out there, residing in unstructured information such as:

In the past, the manual effort required to convert such information into structured data may have precluded its extraction and use. However, tools are available that can intelligently read uploaded documents and do that metadata extraction for you. These data points, while small in isolation, can “roll up” and provide an even richer insight into the level of employee engagement with the program.

In this section we demonstrate how this program effectiveness testing can work in practice. For program design, empowerment and execution standards, we consider in detail the relevant supporting evidence of effectiveness.

There are multiple U.S. and international sources of guidance on the effective design of general corporate and risk-specific compliance programs. For the selected compliance program element, these can be distilled into a series of generic and company-specific design standards or “hallmarks”, and grouped as follows:

It is perhaps program design standards where the self-assessment narrative is most important. Such narrative serves to complement the program governance materials and other supporting documentation. For example, policies and training materials typically do not address:

And yet prosecutors, regulators, and auditors place significant weight on this kind of supporting program evidence. A review of U.S. government guidance reveals over 40 criteria relating to how compliance training should be designed, delivered, and monitored - yet the evidence maintained is often limited to the training material and metrics relating to training completion.23

The absence of such a narrative, prepared at the time of developing the policy or training material, makes it difficult to defend the adequacy of the program element in future investigations or audits. And creating narratives after the fact is challenging and risky – critical context can be missed or misremembered and could potentially put the company at risk.

A common refrain is that the creation of such a self-assessment narrative might itself be the source of legal risk, particularly if it is not privileged and prosecutors, regulators and litigants have access to it. We submit that the benefits of maintaining such a narrative exceed the risks arising from discoverability. If truly necessary, privileged could be asserted on the basis that the narrative was prepared for the purposes of seeking legal advice from in-house compliance or outside counsel. But doing so could, ironically, undermine the value of the assessment. Firstly, to preserve legal privilege, access to the narrative would need to be more tightly controlled. Second, conducting the assessment through a legal filter could result in its sanitization undermining its helpfulness as an honest assessment of what is and is not working. This is not to say that a conversation about how such narratives should be prepared should not be had.

Other supporting evidence relating to program design include current and archived:

and evidence relating to stakeholder consultation on the above materials.

Assessing the design of a compliance program element according to category (e.g., policies and procedures, training & communications) provides helpful structure, but it does not represent the full picture of design effectiveness.

A supplementary approach is to review how these elements interact with each other in the relevant end-to-end compliance process, and how they interact with related business processes. For example, a review of the design of a company’s sales intermediary ABAC due diligence and monitoring process might involve the review of the:

As noted above, a review of a sales intermediary ABAC due diligence program might be supplemented with the parallel review of related business processes such as inquire to cash.

A compliance program design review should extend to the configuration of the supporting compliance system, and its integration with relevant business systems. Continuing the sales intermediary ABAC due diligence example, this would involve a review of the due diligence platform for:

This might also be supplemented with a review of the company’s CRM and ERP systems as to the management of sales intermediaries, to test if the customer onboarding and inquire to cash processes are working in practice.

“In other words, is the program adequately resourced and empowered to function effectively?”24

The DOJ ECCP covers this in detail, and we do not intend to fully restate the relevant standards here. Instead, we focus on the supporting evidence that can demonstrate the relevant program was set up for success.

At the enterprise level, evidence of board oversight – and the chief compliance officer’s relationship with the board – can be found in board agendas, meeting minutes and the terms of reference of committee(s) that the CCO reports into. Retention of such formal records is typically the responsibility of the company secretary and generally poses minimal concerns in terms of access. If possible, committee minutes should record the fact (if not the substance) of any executive sessions held with the CCO. Similarly, recording basic details (e.g., dates, topics) of any ad hoc engagement with board members can be helpful.

Evidence of board oversight of individual programs or program elements is equally valuable and may require some intentionality as to how and where such evidence is maintained. For example, if a quarterly presentation to the audit & finance committee includes a deep dive on the company’s antitrust compliance program, there would be a merit in storing a copy of those materials alongside all your other antitrust program materials (while respective privilege considerations, if any). Moreover, aspects of a company’s compliance program may be addressed in other board committee meetings. For example, the management of anti-corruption risk associated with engagement with indigenous communities might be addressed in the board’s sustainability committee.

At a minimum this would include communications from leadership on their commitment to compliance, and support for the relevant program. However, ethical leadership in action is much more compelling evidence of tone from the top or middle. For example, has leadership decided to change their go-to-market strategy to manage compliance and other risks? Do they actively participate in meetings reviewing compliance-sensitive third parties or activities? Do they proactively invite ethics & compliance managers to be a member of their business unit or regional leadership team? During meetings do they demonstrably refer to the company’s values and Code for guidance? While capturing such evidence (e.g., strategy presentations, meeting minutes, anecdotal stories) might be more challenging than the logging of tone-from-the-top communications, its demonstrative value of management commitment in practice is significant.

How company leadership designs employee incentives, rewards individual employees for “performance” and disciplines employees for misconduct represents one specific and important proxy for management commitment to compliance. Incentivizing employees to work according to a company’s values, even if that means not meeting sales or other performance targets, is one of the most important preventative measures in a compliance program. As is robust and consistent enforcement of discipline for misconduct.

Having auditable standards and evidence relating to a company’s enterprise level performance appraisal and disciplinary process is important. However, a similar assessment can and should be undertaken at a narrower, tactical, program element level. For example, if you are reviewing the design and execution of your company’s sales intermediary due diligence program, this should involve an assessment of explicit and implicit incentives for the sales team to act in compliance with or violation of the program or applicable laws. Is there a special incentive program for sales teams that include unreasonably high revenue targets? Do the contracts with customers impose performance standards that would incentivize sales or supply chain teams to cut corners? Similarly, are there performance or disciplinary consequences for employees who fail to follow the due diligence process? Are those consequences consistently applied? Assessing and documenting incentives and consequences at a program element level is an important part of your assurance process.

There is much official and industry commentary on the importance of the positioning and independence of the chief compliance officer. Evidence of this should be diligently maintained and can include (a) grade and compensation; (b) extent and nature of contact with the board (including participation in executive sessions); (c) participation in management committees (e.g., compliance, sustainability, disclosure) and leadership team meetings; and (d) early involvement in M&A and other strategic initiatives.

However, other evidence is relevant when considering the positioning and autonomy of the broader compliance team in the tactical execution of individual program elements. For example, in relation to third-party screening and due diligence, does a compliance manager have the authority to reject a new or block an existing third party found to have material compliance concerns? How many third parties have they blocked? Is that authority undermined in practice by business leaders “going over the top” and escalating to senior executives who can over-rule the compliance manager or even the chief compliance officer? During investigations, is there evidence of management seeking to interfere with the conduct or influence the outcome of the investigation?

There is much focus on the completion of cultural health and/or program effectiveness surveys by employees. But junior members of the compliance team and other stakeholder functions are exposed to somewhat unique pressures that may require a tailored approach in terms of being heard. This could be through mentoring or a dedicated survey; the key is that compliance professionals feel comfortablespeaking up about any challenges to their authority and independence, and that those concerns are being addressed.

The cut and thrust of the annual planning and budget setting season can be a testing time for chief compliance officers and their teams. From a documentary perspective, your finance function is focused on the numbers. Maintaining that budget information is important, including how your budget compares with other functions. But a spreadsheet or system-generated report only tells half the story and may even be counter-productive if that is your only maintained evidence of compliance resourcing discussions, and it shows year-over-year decreases. If the compliance budget was supported by an accompanying management presentation, it is important to retain that together with a contemporaneous record of the discussion with management.

It might be tempting to conclude that the absence of specific compliance concerns over time means that the relevant program is working. Without additional program assurance, that would be a dangerous assumption to make. For example:

A perfectly working program is also an elusive, and perhaps unrealistic goal. Instead, focus on gathering more proxies for execution effectiveness to provide you a richer picture of what is working, and what is not. These measures can be grouped into three categories: employee performance, compliance & business process performance and systems & analytics performance.

Monitoring employee activity in relation to the compliance program is the obvious starting point. There is a temptation to jump straight to employee compliance metrics but there are several valuable precursor measures that can offer a richer picture:

These measures collectively provide insight into employee performance with the compliance program under review. Many of these measures of employee engagement and compliance can also feed into broader assessments of cultural health.

Poor execution of compliance and related business processes can have a significantly detrimental effect on program effectiveness. Delays in conducting due diligence may prompt employees to circumvent that process in the future. A failure to communicate outcomes of an investigation to a reporter, or inconsistent administration of discipline, may adversely affect the local speak up culture. A failure to complete required remediation following a compliance audit might increase risk further.

The optimal way to address this is to communicate compliance performance expectations upfront to the team and other gatekeepers. For example, processes, checklists or templates can serve to enhance the quality, timeliness and consistency of diligence, monitoring and investigations. They also enable compliance teams to conduct peer reviews of their respective work or for outside advisors to conduct a consistency review against a defined standard.

To provide additional assurance, the development of process performance metrics is critical. For example, what is the average length of diligence and investigations? What % of audit, investigation or third-party remediation is complete? How many purchase requisitions have been rejected for non-compliance?

Employee perceptions of the compliance program are also an important input and can be obtained via risk assessments, audits and surveys. Compliance teams at some companies utilize net promoter scores to track employee sentiment towards a compliance process.

Finally, tracking the performance of relevant systems and analytics is important. For example:

Ideally the tracking and reporting of systems/analytics performance would be addressed in service level agreements with the relevant internal function or third-party service provider.

It is worth spending time thinking carefully about what form your program assurance will take:

Innovative technology providers are now utilizing artificial intelligence to undertake the initial assessment of a company’s performance against pre-defined audit standards by undertaking the initial review of supporting evidence.

In determining this, it is worth reflecting on what functionality you wish the tool to have either now or in the future. For example:

As evidenced above, your assurance tool can be as simple or advanced as you require, mindful of your design and evidentiary requirements.

With program assurance standards defined, narratives maintained and supporting evidence organized, you will reap multiple benefits:

The act of bringing together program assessment narratives, metrics and supporting documentation, and utilizing generative AI to interrogate it, can unlock even more value. By way of illustration, several gen AI use cases are provided below:

In recent years we have been accustomed to the periodic elevation of U.S. prosecutor expectations with regards to compliance programs. The current pause in FCPA enforcement might temporarily quiet the drumbeat of government expectation, but this is not the time to slow down.

The case for continuous improvement does not rest solely on government enforcement. It is reinforced by an expanding set of risks, and the expectations of a broader group of stakeholders each with their own unique evidentiary and assurance requirements.

But, in the peace of the stilled drums, we do have an opportunity. A moment to reflect on what’s working, what’s not, and where we can experiment, simplify, and improve. This article has argued for a more intentional and sustainable approach to program effectiveness, by explicitly considering and documenting the standards and evidence by which compliance programs should be assessed. We should proactively ask ourselves:

Doing this well requires partnership—with Legal, Finance, IT, HR and other functions. This call to action also extends to outside counsel, auditors, technology and other service providers that support ethics & compliance teams. Providers must question if their products and services genuinely facilitate the full effectiveness assessment of their clients’ compliance programs:

A compliance program does more than reduce risk. It builds trust with employees, communities, investors, and other stakeholders. It gives companies the confidence to operate with integrity in an increasingly complex world. But that trust and confidence must be earned and sustained through evidence. Testing the effectiveness of your compliance program is critical to both and serves as a catalyst for continuous improvement. Now is the time to test whether your compliance programs are truly working.

1 U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) Criminal Division Evaluation of Corporate Compliance Programs (ECCP) (2024). The September 2024 version of the ECCP includes this question: “Measurement – How and how often does the company measure the success and effectiveness of its compliance program?” However, the concept of compliance program effectiveness in U.S. corporate criminal enforcement is not new. The U.S. Sentencing Commission, Guidelines Manual, § 8B2.1 (USSG) includes the following: “The organization shall take reasonable steps...to evaluate periodically the effectiveness of the organization's compliance and ethics program”, which was first included in the 2004 version of the Guidelines. The model DOJ Non-Prosecution Agreement (NPA) and Deferred Prosecution Agreement (DPA) require the production of a workplan which shall “identify with reasonable specificity the activities the Company plans to undertake to review and test each element of its compliance program”; the preparation of an annual report which includes “a complete description of the testing conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of the compliance program and the results of that testing” with the third annual report including “a plan for ongoing improvement, testing, and review of the compliance program to ensure the sustainability of the program.”

2 Principles of Federal Prosecution of Business Organizations in the Justice Manual (JM) JM 9-28.300; USSG §§ 8B2.1, 8C2.5(f), and 8C2.8(11)) as summarized in the DOJ ECCP.

3 Presidential Executive Order February 10, 2025 “Pausing Foreign Corrupt Practices Act Enforcement to Further American Economic andNational Security”.

4 Bribery Act 2010 (UK), c.23, §7, which creates a strict liability offence for commercial organizations that fail to prevent bribery by associated persons unless “adequate procedures” are in place; Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act 2023 (UK), c.56, §199, which introduces a new corporate offence for failure to prevent fraud, applicable to large organizations with a compliance-based defense; Law No. 20.393 (Chile), Ley sobre Responsabilidad Penal de las Personas Jurídicas (2009), which establishes corporate criminal liability for offences such as bribery and money laundering where companies fail to implement adequate compliance programs; and Criminal Code of Canada, R.S.C., 1985, c. C-46, §§22.1–22.2, which imposes liability on organizations that fail to take reasonable steps to prevent criminal offences by their representatives.

5 CTPAT U.S. Importers Minimum Security Criteria (CBP Publication 1747-0422). Also see CTPAT “Forced Labor Requirements Frequently Asked Questions”, last updated June 2023.

6 The UFLPA is enforced under Section 307 Tariff Act of 1930, codified at 19 U.S.C. § 1307, which prohibits the importation of goods mined, produced, or manufactured wholly or in part by forced labor, including forced or indentured child labor. See also CBP “Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) Enforcement: Frequently Asked Questions”.

7 Modern Slavery Act 2015 (UK), c. 30, § 54; Modern Slavery Act 2018 (Cth) (Australia), Part 2, §§ 13–16; Fighting Against Forced Labour and Child Labour in Supply Chains Act, S.C. 2023, c. 9 (Canada), §§ 4–11.

8 Key ISO standards relevant to ethics and compliance programs include: ISO 37301:2021 (Compliance Management Systems – Requirements with Guidance for Use), which provides a certifiable standard for establishing, developing, implementing, evaluating, maintaining, and improving an effective compliance management system; ISO 37001:2016 (Anti-Bribery Management Systems), which outlines requirements and guidance for implementing measures to prevent, detect, and respond to bribery; and ISO 37002:2021 (Whistleblowing Management Systems – Guidelines), which offers a framework for receiving, assessing, and managing whistleblower reports while ensuring confidentiality and protection from retaliation.

9 For example, the Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA) Standard for Responsible Mining includes specific ethics and compliance-related requirements. These include measures to prevent corruption and bribery (Chapter 1.6), such as prohibitions on facilitation payments, obligations to implement anti-corruption policies, and expectations for training and reporting. IRMA also requires that sites implement operational-level grievance mechanisms that are accessible, transparent, and effective (Chapter 2.10), aligning with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. See: IRMA Standard for Responsible Mining, Version 1.0 (2018), with draft Version 2.0 currently the subject of consultation.

10 Examples include Ecovadis, Sustainalyticsand the Dow Jones Sustainability Index.

11 For example, the European Commission Directive 2022/2464 amending Directive 2013/34/EU as regards corporate sustainability reporting known as the Corporate Reporting Sustainability Diligence Directive (CSRD) requires companies to implement internal control systems for sustainability disclosures, many of which touch on ethics and compliance (e.g.,anti-corruption, due diligence, grievance mechanisms); World Business Council for Sustainable Development, Internal Controls over Sustainability Reporting (ICSR): Executive Summary (2023).

12 World Bank, Procurement Regulations for IPF Borrowers (2020), Sections 3.14–3.17 (mandating integrity, fairness, and transparency in procurement and allowing for enhanced due diligence in high-risk contexts); U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for Federal Awards, 2 CFR Part 200 (requiring internal controls and compliance with applicable laws and regulations as a condition of federal grant funding); OECD, Recommendation on Public Integrity (2017), para. IV.15 (encouraging public entities to conduct integrity screening of recipients of public funds, including pre-grant due diligence).

13 The U.S. Department of Justice takes a similar risk-based approach when reviewing the effectiveness of compliance programs. In the ECCP they state: “We recognize that each company’s risk profile and solutions to reduce its risks warrant particularized evaluation. Accordingly, we make a reasonable, individualized determination in each case that considers various factors including, but not limited to, the company’s size, industry, geographic footprint, regulatory landscape, and other factors, both internal and external to the company’s operations, that might impact its compliance program.”

14 Examples include DOJ & SEC, A Resource Guide to the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (2nd ed., 2020); DOJ, Evaluation of Corporate Compliance Programs in Criminal Antitrust Investigations (November 2024); European Commission, Compliance Matters: What companies can do better to respect EU competition rules (2013); U.S. Department of the Treasury,and Office of Foreign Assets Control, A Framework for OFAC Compliance Commitments (2019)

15 Examples include OECD, 2021 Anti-Bribery Recommendation (Annex II: Good Practice Guidance on Internal Controls, Ethics and Compliance); OECD, Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct; OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct, and the Guidelines on Anti-Corruption and Integrity in State-Owned Enterprises; World Bank, Integrity Compliance Guidelines (2020).

16 See footnote 8, supra.

17 e.g., CSRD

18 Integrity Bridge maintains a list of ethics & compliance benchmark reports which is by clicking here.

19 DOJ ECCP; U.S. DOJ, Evaluation of Corporate Compliance Programs in Criminal Antitrust Investigations (November 2024); European Commission, Compliance Matters: What companies can do better to respect EU competition rules (2013)

20 See Chen, Hui & Soltes, Eugene, Why Compliance Programs Fail—and How to Fix Them, Harvard Business Review (March–April 2018). Chen and Soltes highlight that compliance metrics frequently measure inputs rather than meaningful outcomes or behavioral changes, limiting their value in assessing real-world effectiveness; Also see Soltes, Eugene F. "Evaluating the Effectiveness of Corporate Compliance Programs: Establishing a Model for Prosecutors, Courts, and Firms." NYU Journal of Law & Business 14, no. 3 (Summer 2018): 965–1011.

21 See Moosmayer, Klaus, Ethics & Integrated Assurance: The Challenge of Building Trust, Risk & Compliance Magazine (April 2024). Moosmayer recommends that compliance and audit functions adopt a joint taxonomy for root cause analysis and remediation activities, enabling consistent classification and reporting to improve transparency and cross-functional assurance.

22 For practical considerations relating to the development of ethics & compliance data analytics programs, please see the Applied Compliance section on data analytics, which contains several articles and podcasts on this topic: www.appliedcompliance.com

23 United States Sentencing Guidelines Manual § 8B2.1; U.S. DOJ, ECCP (2024); U.S. DOJ, Attachment C,; U.S. DOJ and SEC, A Resource Guide to the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (2nd ed., 2020); U.S. DOJ, , Evaluation of Corporate Compliance Programs in Criminal Antitrust Investigations (2024); U.S. Department of the Treasury, Office of Foreign Assets Control, A Framework for OFAC Compliance Commitments (2019); U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of Inspector General, General Compliance Program Guidance (2023).

24 DOJ ECCP